By: Michele Wood, Director of Research, Valbridge Property Advisors | Houston

September 25, 2020

Like many parents this fall, my husband and I packed up our car and drove our 18-year old daughter 1,225 miles to move her in for her freshman year of college. Like most universities and colleges, my daughter’s campus was open, though most classes had moved to online or hybrid formats to try and limit exposure to the virus. After a tearful goodbye, we left her there to start her new life as a college student. What we didn’t expect after that day in early August was that by September 1st she and nearly all the other students housed by the University on campus would be told that all classes were now exclusively online and they were shutting down the dorms.

Many of her classmates simply moved home when they got the news, but many more wanted to stay. They had been on campus nearly a month and wanted desperately to try and salvage what they could of their college experience for the semester, and for the whole academic year. My daughter asked if she and her new friends could move off campus, and we agreed.

In late spring and early summer, headlines regarding the student housing market painted a bleak picture. “Campus Outbreaks Have Muddied the Picture for Student Housing,” “The Next Falling Domino: Student Housing,” and “Fall Pre-leasing Trailing 2019 Rate.” Browsing the websites of the properties my daughter was touring that weekend, I saw lots of vacant units listed and wonderful concessions (from the tenant’s perspective, anyway). Offers lit up the screen like 1 free month, $1,000 gift card with signed lease, a free iPad mini. It surprised me after seeing those when my daughter called from the first property, saying they had no available units. Weird. Next one, same thing. Third one, all full. They finally found the four bedrooms they needed at the 6th property that they toured in a 5-bed, 5-bath unit, and it was the last one available. The manager helping my daughter and her friends reported that he had signed 51 leases in the 24 hours before they arrived. This was three weeks after school had begun.

Even before the pressures of COVID started to panic school administrators and students, the 175 largest universities in the United States could only house 21.5% of their undergraduates. With all the uncertainties looming over the summer, many schools decided to de-densify their on campus rooms, moving triple and even double occupancy rooms to singles. In addition, they saw need to hold rooms empty, often a whole building, to serve as quarantine space for students who tested positive once on campus or were in close contact with a positive case. These measures put further pressure on already stressed room availability for on-campus options.

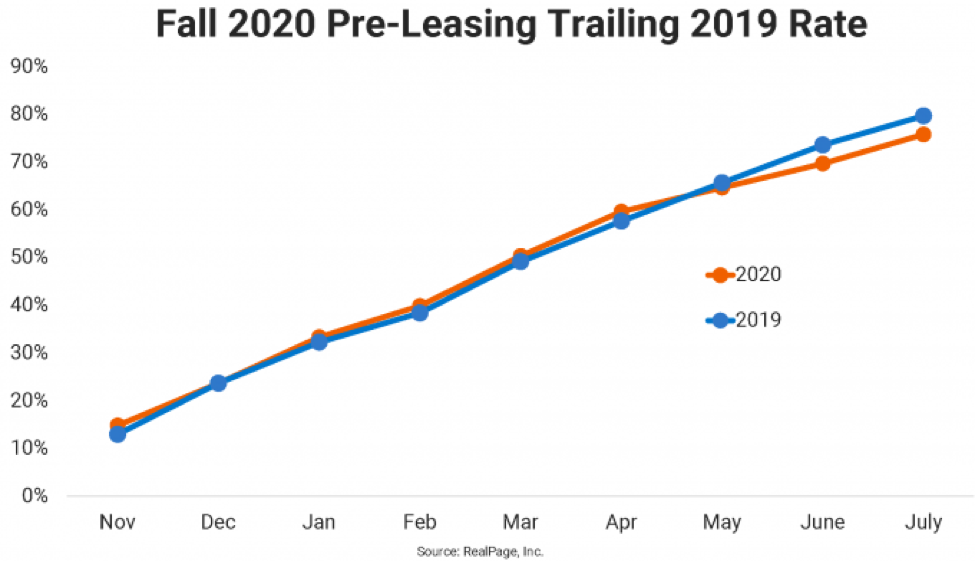

The pandemic is upending the metrics and forecasting models for many property sectors. With parents concerned about the virus, about paying for an on-campus experience when classes are virtual, with concerns about the economy or job security, it seemed reasonable to question the stability of the student housing market for 2020-2021. Pre-leasing is strongest for these properties in the early spring, which was just when colleges across the country started to shut down and send kids home. It would make sense that it would be impacted, especially as summer brought higher infection rates and more uncertainty than expected. According to RealPage, as of July, 82.2% of beds at the core 175 universities tracked were pre-leased for Fall 2020. That was about 340 basis points below the same month in 2019.

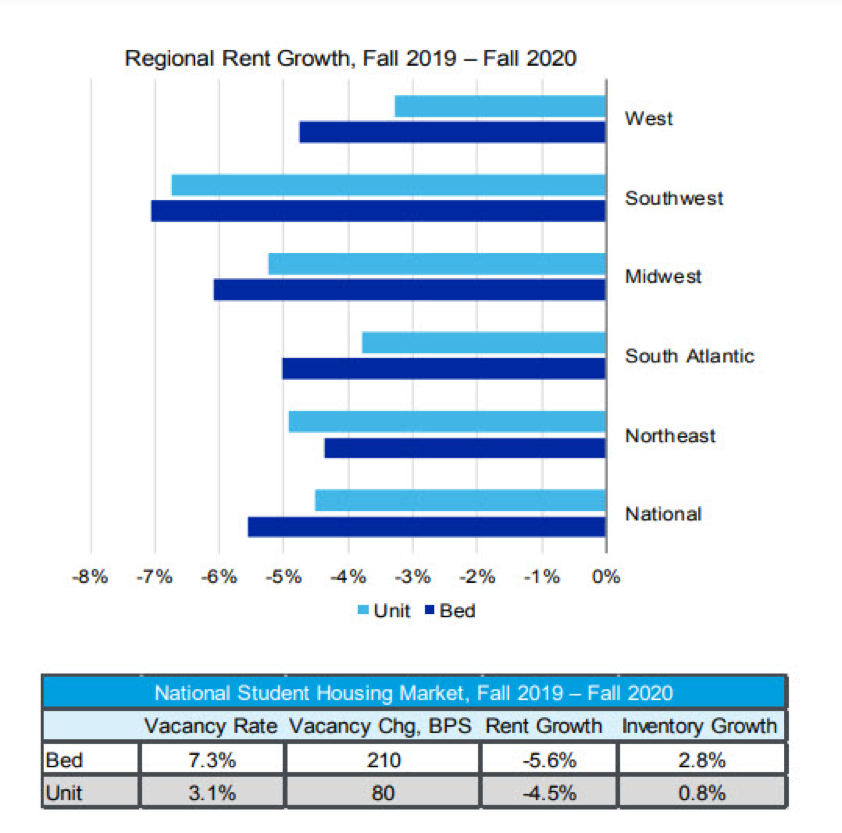

In response to the weaker pre-leasing period and the uncertainty of demand, student housing operators have not raised rents as high as they typically do for the year. Some have held rates steady or added concessions that effectively reduce the rent. By July of this year, effective asking rents had ticked down to just 1.1% above last year. However, if more universities start to experience what happened in North Carolina, with off-campus housing suddenly seeing an influx of demand as a result of dorms closing unexpectedly, we may see the rates tick up to keep pace with increasing demand. Of course, property location determines how likely these properties are to suffer from closures and demand changes, and late leasing creates a lower overall EGI for the property when terms are pro-rated.

Source: REIS, Real Estate Solutions by Moody’s Analytics

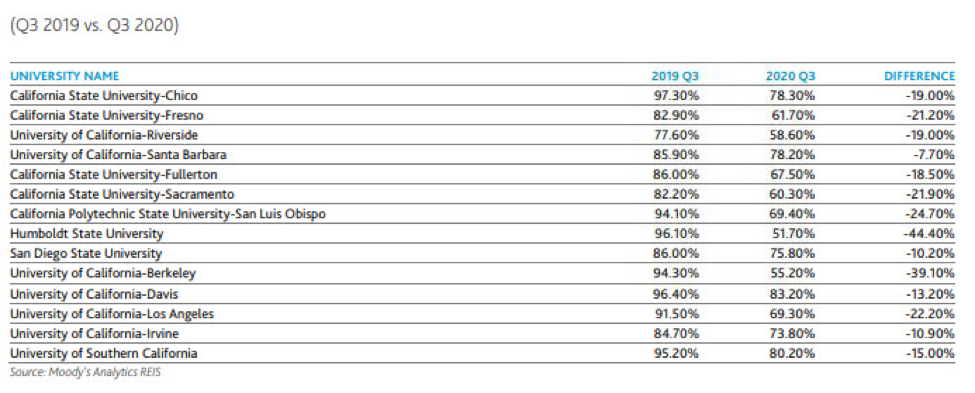

The sector performance is not spread evenly across the country. For example, California universities announced early that they would be fully online which impacted properties around those schools more dramatically. With no possibility of an on-campus experience, whether residential or academic, many students reduced their course loads or opted for gap years instead. Pre-leasing activity there was down 7 to 44% between Q3 2019 and Q3 2020, according to Moody’s Analytics/REIS.

Even in schools that have moved students in and are still housing them on campus, there are rumblings of disappointment and questions of canceling housing contracts to seek off-campus options. A friend whose son just started at the University of Arizona is looking into getting him out of the dorm as the restrictions in place (no visitors at all allowed in the building, no one but a roommate can be in your room, room doors must remain closed at all times, etc) are making it difficult to meet and connect with other students or even form study groups and find extracurricular clubs. Like our family, they are willing to pay a little more if necessary for off-campus rentals to ensure that their child can have some of the residential college experience salvaged.

According to RealPage, August 2020 occupancy rates for student housing beds across the US were 88%. That’s only slightly lower than the 91% occupancy for August 2019. Another source told me that two of the largest student housing operators are running at over 90% occupied for this academic year. The vacancies are in higher density units with 3 and 4 bedrooms, but single and double bed units are full. Parents and students are attracted to this option if dorms close or are not available as purpose-built student housing is newer with better air circulation and filtering and most have private bathrooms for each bedroom, providing less contact if a roommate becomes exposed or sick. Laura Formica of Homestead Companies reported that they have hit 100% occupancy for their units at OSU for this academic year.

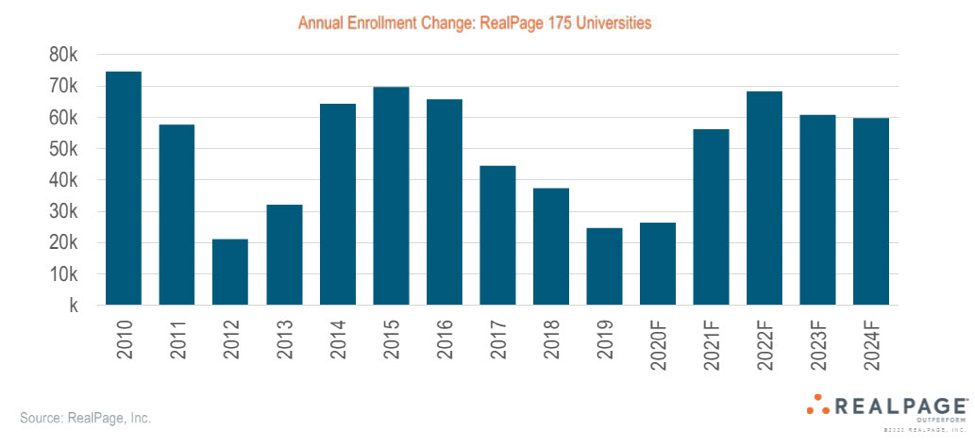

Student housing operators are savvy at choosing their locations and construction timelines. While the virus has upended many aspects of the pipeline for properties yet to be built, there is industry optimism in the model. Most people expect colleges to resume a more or less “normal” routine by Fall of 2021, which would help bring demand back up to the rates anticipated in Fall of 2020 that were derailed by the pandemic. International students take up a considerable portion of student housing beds, even in spite of recent increased barriers to immigration and student visas. That trend is expected to continue. Demand is expected to pick up in Fall 2021 as well when the 10% of students who have deferred enrollment from Fall 2020 register for classes and move to now-open campuses. Of course, markets where white collar job loss stays high are at risk for lower demand.

As for transactional data, market participants are less clear. The first quarter of 2020 saw $1.7 billion in student housing transactions, which was 13% higher than Q1 2019, according to a CBRE Roundtable report. After the first quarter, however, deals have frozen up as market participants wait to see how occupancy and rent collections go. Moody’s reported a wide bid/ask spread as the likely culprit for the deal stagnation. Buyers want a discount for the risk, and sellers are reluctant to sell at a discount, particularly if they see this as a temporary drop in occupancy. One hedge that may attract buyers even if rent growth doesn’t recover quickly is that most of the properties are located adjacent to, or very nearby large universities, many in decent sized markets. The location and land values can be considered in exit strategies down the line with many properties able to convert easily to traditional multi-family or redevelopment sites once they are functionally obsolete.

Some markets were facing oversupply before the pandemic hit, causing distress in the properties competing for students. According to DBRS Morningstar, the delinquency rate for student housing loans increased from 0.2% in January 2018 to 3.8% in April 2020, going to 9.5% in May. Loans sent to special servicing went from 1.7% in January 2018 to 4.6% in April 2020. Jaclyn Fitts of CBRE wrote in the State of the Market Student Housing Report in June “Delinquency is highly concentrated in a select group of owners and does not indicate market wide concerns. With the strong collections seen in the sector in late spring, CBRE does not believe COVID-19 is a driver for any distress in the sector, and select owners are taking advantage of the potential to renegotiate their loans in oversupplied markets.”

Crystal balls are hard to come by in real estate, and never more so than in the current year. For properties near schools like Michigan State University, which announced a week before move-in was scheduled to start that they were going fully virtual and would not move students onto campus, the shut down was a blessing in disguise. “We captured 170 leases the first weekend after the university gave notice to those students to vacate,” reported the president of Pierce Education Properties in a September 8 article. As a consultant for student housing development told me, “This was one of the hottest sectors in real estate before the pandemic. Now it’s just hot instead of red-hot.” In 2020, hot may be good enough for many investors.