By: Michele Wood

Co-living is one of the prevalent buzzwords in commercial real estate this year. In a world where the sharing economy has disrupted the hotel and office sectors, it’s no surprise that the trend has moved into our homes. Co-living and its cousin co-housing are joining communes, condos and co-ops as distinct ways in which unrelated people live together. How are these trends impacting the housing market? To answer this question, we start with a brief history of how people live and live together.

Modern housing innovations have solved many problems, but have created others. Human psychology is designed for social connection and operating within a community. Many adults report feeling lonely and socially isolated, and co-housing and co-living are a response to the need to connect. Julianne Holt-Lunstad, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Brigham Young University, did a meta-analysis of 148 studies of the benefits of human connections and communities. She writes, “Adults who are socially isolated have a 50% greater risk of dying from any cause within a given time frame than people who are more connected.” Some of these feelings of disconnection and isolation contributed to the rise of communes and cult communities in the second half of the 20th century, many with tragic outcomes. These trends are also responses to demands on time and money because sharing space helps make it more affordable, as we will see later.

Though it may seem new, communal living is actually a return to our roots. Even long after abandoning tribal lifestyles, unrelated people often lived in large groups under the same roof. During the Middle Ages, single family households were rare, and it wasn’t until the 12th century in western Europe that households came to be organized around couples and their children. Even these households, however, held more than the nuclear family and often included other people’s children, widows, orphans, elderly people, servants, boarders, visitors, friends, and assorted shirt-tail relatives.

Living with strangers and friends was very common in Europe, and people would often treat houses like public property. As John Gillis described the scenes in his 1997 book A World of Their Own Making: Myth, Ritual, and the Quest for Family Values, “People entered without knocking, even without acknowledgement. It was often difficult to tell which family belonged where…in big as well as little houses, the constant traffic of people precluded the cozy home life we imagine to have existed in the past.”

By the 1500s, a more familiar view of the household began to take shape, consisting of a father, mother and their biological children. In large part due to the Reformation, religious leaders encouraged the break with the Catholic church as the center of life, replacing it with the “godly household” and a more personal relationship with God and religion. But even with this cultural shift, single family households were still uncommon due to the expense and labor of keeping one up.

It wasn’t until the Industrial Revolution that households started to hold only family and not friends or boarders. Factory work meant that large households were a liability, not a necessity as they were for farmers. As offices replaced factories in the 20th century, modern technological advances made it more practical for a single family to run a home. Households shrank down to the nuclear family, and suburban subdivisions created environments where people were more cut off from their extended families, friends and neighbors than they had ever been in the entirety of human history.

Co-housing and co-living may suggest images of hippie communes, but they are a far cry from the cult-figure groups that created isolated communities in the jungles of Guyana or the mountains of Oregon. Co-housing can be traced to Denmark, where the first “living communities,” or bofaellesskaber, opened in 1970. The idea came to the United States in 1991 with Muir Commons in Davis, California.

Co-housing is a specific type of “intentional community,” designed with a connection to neighbors as a primary goal. This usually consists of small private homes, generally numbering between 15 and 35, that share some common space, often including a main building with a large dining room, commercial-size kitchen, and community rooms. The community is master-planned to encourage interaction, with homes sited in close proximity and facing each other across footpaths rather than streets. Cars are stowed in the backs of houses or in nearby parking areas. Homes are owned and managed by the residents and decisions about community rules and maintenance are consensus-based.

Communities can be inter-generational or age-specific (usually “active adult”), or they can be organized around shared values such as environmental concerns. Some are designed to bring together people with common interests or needs such as single mothers looking for support. Other communities have gotten creative with resident populations: in Chicago, a neighborhood called Hope Meadows has retirees living together with at-risk foster kids.

Chores are arranged communally for common spaces, or may be contracted out with association dues. Often, more than just space and chores are shared. The density that results from co-housing allows single-family households to pool their resources when meeting needs that can be resource-intensive, but which only occur during certain phases of life, such as childcare and elder care.

Meal-sharing is a primary benefit for many residents, both for the sense of community when eating together, as well as lightening the burden of meal preparation and cleanup. In one community, the main dining room seats 28 people plus guests, and they dine there three times a week. The large adjacent kitchen holds teams of three that do the cooking, so with 17 adults in the community, each adult cooks once every six weeks and helps with general prep and cleanup twice in that time period. The rest of the meals can just be enjoyed by showing up.

Co-housing is a modern attempt to balance the need for community with the American desire for privacy. Unlike the sometimes notorious communes of the 1960s and 1970s, residents in co-housing communities are not looking to “tune in, turn on and drop out” of society, and a visitor will not find any gurus or robed leaders.

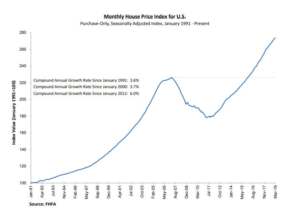

Instead, it appeals to families, retired couples, or older single people seeking to establish a connection to a group of people. Co-housing residents want smaller home footprints, less property upkeep, and they want to be engaged with friends and neighbors on a day-to-day basis. With demographic trends moving toward more mobility, extended families are often far apart and many people do not live in the towns where they grew up. Relocation and distance lead to disconnection, and co-housing communities can help re-create that sense of connection to community. Maintaining a larger-than-needed single family home and yard can be a drain on finances, especially after child-rearing years are over. At the same time, that maintenance can be a burden on the schedule of busy working parents. Recently, the strong economy and the high number of homes for sale have not translated into strong sales. This has been caused by slowly rising mortgage rates and the price points of the homes on the market. In many areas, the median price for a single family home is out of reach of most middle-class incomes. The affordability rates become more bleak when a down payment below 20% is considered. More and more, fewer potential homebuyers are able to come up with large down payments as other types of debt (student loans, for example) and higher expenses such as health insurance premiums make saving cash difficult.

Co-living, on the other hand, works in an entirely different way, and appeals to a different demographic. In co-living communities, residents rent space in multi-family buildings, sharing common areas such as kitchens, living rooms and game rooms while occupying a private bedroom and en-suite bathroom. It is similar to an upscale college dorm, and the spaces come with amenities such as wi-fi, utilities, housecleaning and catered parties. Units are fully furnished and don’t require long leases, often offering month-to-month options. Billing, maintenance and other planning are handled through an app.

This product primarily appeals to younger single people, usually in their 20s to 40s. Residents can be young professionals, graduate students, or the newly divorced. The ability to move into a new city easily and quickly is appealing, especially with ready-made space, companions and services on more flexible, shorter terms. Many young professionals want more mobility in their careers and lives while living in cities with skyrocketing rental rates. Co-living can offer Class A space without hassles such as finding furniture, roommates and utility hook-ups, often at 20 to 30% less than a private 1-bedroom apartment.

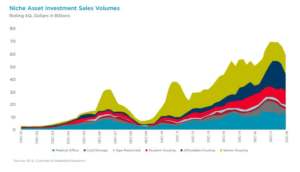

One of the challenges facing the co-living industry is the perception that it is a niche market with little appeal to investors. It may not stay a niche market for long, though. Many institutional-grade asset classes such as self-storage and senior housing began as niche assets just a decade ago.

Currently, funding for co-living companies is divided into operations (venture capital or angel funding for building platform and features) and property (debt and equity for developing ground-up projects. Many co-living companies do not own their real estate but operate on “asset-light strategies.” Quarters, a leading co-living developer, signs 10-year leases with two 5-year options in build-to-suit properties.

Co-living isn’t just a more affordable Class A space for renters. From the operator’s standpoint, you are getting more rent per square foot than a traditional unit. One community, Alta+, operated by Ollie in Long Island City, New York, reports that their units earn an average of 44% more income in rent per square foot than the conventional units they manage in the same building. Those higher rents can typically translate into an operating margin that is 30 to 50% higher than conventional multi-family properties, according to Matthew Polci of Mission Capital Advisors. This superior performance is starting to attract interest from banks and more traditional lenders.

Rents for the co-living units vary by location and operator. WeLive, the co-living operation of the co-working company WeWork, offers fully furnished studio units in Manhattan starting at $3,175 per month. Average traditional studio units in the area run $3,161 per month without the furnishings and other amenities. Common, one of the largest co-living operators, offers units in Crown Heights starting at $1,340 per month, compared to the average traditional unit price in Brooklyn of $2,722 per month, according to an April 2019 report from the brokerage MNS.

So far the funding for projects is nearly all private. Quarters has raised $1.4 billion in equity and debt for co-living projects globally, with $300 million earmarked for projects in North America. Currently there are 3,053 beds already online in the United States among the six largest players in co-living: Common, Ollie, Quarters, Starcity, WeLive, and X Social Communities, and that group reports a combined 9,300 beds in the pipeline. Demand seems strong. In 2018, Common had more than 14,000 applications for just 700 open beds nationwide.

Since the property type is so new, there is little information available to lenders, investors, developers and appraisers. Expense histories, occupancy rates, development costs and rates of return are going to be watched carefully as this asset class matures. Will conversions from existing space prove cost effective, or will ground-up development prove wiser? Is the business model scalable, and how well does a co-living space interact with traditional units in the same building? How will changing demographics over the next decade change the demand characteristics for this property type? How are the intangible elements of the properties identified and valued? How much conventional demand will the properties siphon away from single family subdivisions and traditional multi-family projects?

As more capital is deployed for development over the next five years, investors and other stakeholders in the market will have more information on this niche asset, determining if this is a residential trend to stay, returning us to our communal roots, or whether this was just a temporary market experiment. In the meantime, best to hold off on drinking any free Kool-Aid.