By: Michele Wood, Director of Research, Valbridge Property Advisors | Houston

When my husband and I were first married and living in Arizona, we dreamed of moving out of our crowded 1-bedroom apartment. We had both finished our graduate degrees and were gainfully employed, but student loans and starter salaries had kept us from saving much for a down payment on a home. Instead of toiling in our third story garden-style unit, we chose to rent what was being called a “casita” in a new development not far from our traditional apartment complex. Each casita was freestanding and had between 1-3 bedrooms and a private, walled backyard. Parking consisted of assigned spaces in a common area lot and the community had a swimming pool for use by residents. We chose a brand new, 2-bed/2-bath, unit with 12-foot ceilings, clerestory windows, an island kitchen and a jetted tub. Suddenly we had privacy, light, an in-unit full size washer and dryer and a built-in wine rack. We loved it.

What we did not realize 20 years ago was that these communities, now commonly called “Build-to- Rent,” (BTR) or build-for-rent, or horizontal apartments, were soon to become the new hot trend in multi-family development. Build-to-Rent communities offer the lifestyle of suburban, single-family neighborhood living, but are constructed exclusively for rent and are managed by a single management company, similar to traditional multi-family. In most cases, the communities are self-contained and are on one parcel of ownership.

Who are the renters?

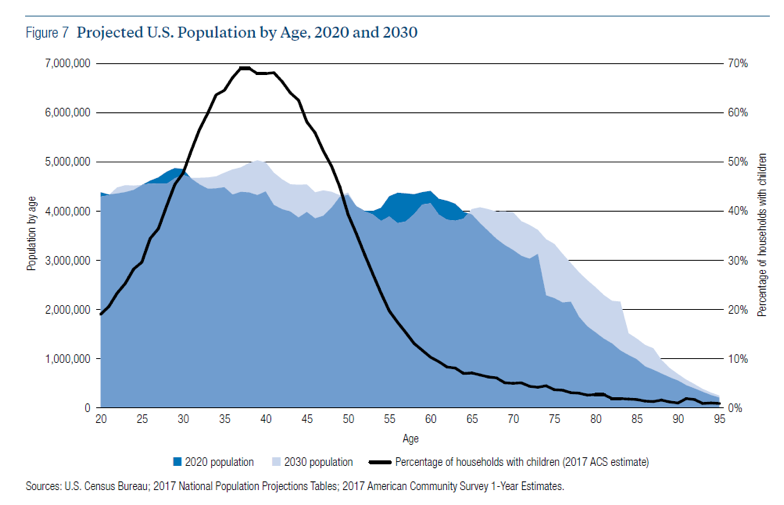

Between the middle of 2019 and the middle of 2020, 1.2 million new households were formed in the United States. More than 50% of them were renters. This percentage is expected to go to 60% in the next decade. At the same time, single family housing starts are 13% below the historical average. Single Family Residential (SFR) homes are critically undersupplied at lower price points, putting strain on new households without wealth equity to use for purchasing a home. Existing SFR’s are over 19 years old on average, creating a lack of supply of new product that’s both desirable and affordable, especially for younger renters.

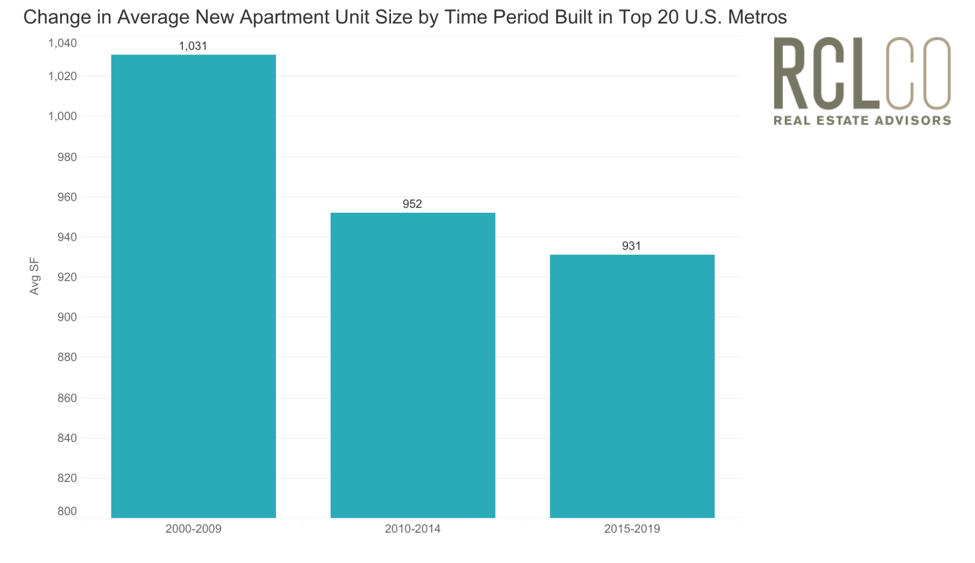

Demographically, families that rent are just as large as families that own, but overall, traditional multi-family space is smaller than a single-family home and is getting progressively smaller.

The trend was originally responding to the numbers of Millennials moving to urban centers as well as aging Boomers who were looking to downsize. What developers missed, however, besides the upcoming pandemic, was that aging Millennials were forming families and beginning to need more bedrooms in places with better schools. Saddled with record student debt and lacking the requisite down payment necessary, as well as having already developed a taste for new housing finishes and amenities such as stone countertops, wood flooring and stainless steel appliances, many are not willing to trade square footage for outdated interiors. They want space and style. Enter build-to-rent.

According to one developer with over 10,000 units already under his belt, his renters look more like traditional homeowners. Forty-five percent have college degrees, 600 is the average credit score, and $82,000 is the average household income. Many are replacing a “starter home” with a BTR home. With one third of all renters in the United States heading families, and 64% of the housing stock over 50 years old, there is demand for an updated product type.

Why BTR?

What are the advantages to a developer building BTR over traditional multi-family or SFR subdivisions, which are the two main competitions of residential demand? Compared to single family subdivisions, the efficiencies in BTR are better. Consider that there are only a few floorplans in each community (typically a 2-unit/1-bedroom duplex, a 2-bedroom unit and a 3-bedroom unit) and each floorplan is going to have identical interior appointments, appliances and pre-designed exteriors. With SFR development, each homebuyer is choosing from a wide array of options and upgrade packages. A BTR developer does not have to pay agent commissions on each home sale, and there are no construction defect litigation costs, which in some states can add five figures to the average cost of a new home.

Comparing BTR to traditional multi-family is less obvious. Some efficiencies are lost in the addition of exterior walls and less density on the site. What emerges is the timeline advantage. Compared to single family development, there is no longer any takedown phasing. Similarly, the cycle time for BTR from cash outlay to income is shorter than traditional multi-family. This means a smaller risk window for lenders as phasing is much easier — each unit can be leased as soon as it is completed whereas apartment units must wait for the whole building to be complete before welcoming the first tenant. For now, the product type is so new that many of the largest traditional lenders are still skittish while they wait for more data. According to developers, private capital has been more comfortable with lending but this has led to higher borrowing costs, typically calling for 75-85% loan to cost and 9 -11% interest rates. This can be mitigated by higher rents. BTR units typically command a 5-20% premium on a rent per square foot basis over non-professionally managed SFR rental sector. Rents are 10-15% higher than conventional multi-family, on average.

What are the challenges?

Nervous lenders aren’t the only challenges to BTR. Because of the specific demographics needed to tenant the projects and the demands of those renters, projects almost universally need to be “urban adjacent,” making land prices higher. As COVID continues to create more work-from-home professionals, the urban proximity need may soften and open up more suburban and even fringe rural options for development. But this brings its own hurdle: neighbors often oppose rental communities, no matter how upscale. The higher density of BTR versus traditional single family, the worry about traffic, school crowding, and the stigma of renters versus homeowners can cause NIMBY protests and delay or even derail projects. Of course, many area homeowners don’t realize that like upscale MF communities, tenants must pass background checks and can be evicted for violations of conduct. This is not the case in neighborhoods where anyone with a loan can purchase the house next to you and little can be done easily about nuisance neighbors.

Developers have also found that entitlements can be tricky in some areas. This can delay projects’ timelines as municipalities get overwhelmed because the velocity is much higher than with SFR development. Each unit must be inspected and permitted as it is built, but the units come out of the ground faster than SFRs, placing burdens on inspection staffing schedules.

What makes 2020 the year of BTR?

One notable headline in the second half of 2020 is that of the red-hot single family residential sale market. With people seeking more space and distance during social distancing and varying stages of “stay at home” orders, urban cores are emptying as workers and families move to suburban and rural areas. Many of these people are not expected to return to their former living situations. Combined with stable white-collar employment and record low mortgage interest rates, SFR supplies are tight in many markets and agents are reporting bidding wars for active listings. While employment has been somewhat stable for white collar workers, incomes in some industries have come down slightly or stayed stable, so while home prices have skyrocketed, the ability of many would-be homebuyers to purchase has been out of reach. But buyers are not the only ones seeking less density and more square footage. According to one BTR developer, demand is “off the charts” this year. Their ability to meet the demand has been somewhat hampered by construction delays and funding pauses in capital markets. The capital faucet, however, appears to have opened up as investors are looking for targets. While other real estate sectors are still pausing, multi-family and BTR are good options. According to Brad Hunter of Hunter Housing Economics, “(BTR) is a money magnet right now.”

What are the numbers?

John Burns Consulting offered the following breakdown on a “typical” project in a recent webinar:

Land Cost: $2 to $6/SF

Development Cost: BTR Units: +/- $190,000 per acre

Construction Costs (Looking to yield 100 to 250+ units):10-12 units per acre at 975 SF home on average, cost after land purchase and improvement is $105 to $115/SF

The construction timeline can vary based on many factors, especially the municipality. For example, in California the time from groundbreaking to rent collection is typically 2-3 years. It is 12-18 months in Texas, and in other sunbelt states, you can expect anywhere from 9-24 months according to Mitch Rotta at TriCor Homes.

2020 is the year of BTR

ULI published a study on Family Rental Housing this year, projecting that demand will outstrip supply in the coming years. They expect that 210,000 units need to be constructed over the next 5 to 10 years to keep up with the demand.

All this demand is starting to catch the eyes of the investors, as cap rates are the same as multi-family cap rates right now. Rent growth is stronger in the BTR sector than traditional multi-family overall, with 7 to 8% escalations per year in the strongest markets. In the 4th quarter of 2020, cap rates are between 4 and 6%. The largest BTR community by unit count just sold in Glendale, Arizona for $265,000 per unit for 313 units and a 5.5% pro forma cap rate, according to Costar. The price comes out to about $265/SF for the property which includes a fitness center, a pool area with cabanas and private, fenced backyards for each unit. With building costs shown above hovering under $125/SF, the profit margin is attractive to developers.

A representative from a development company that has recently opened a 151-unit community in Austin called Urbana at Goodnight Ranch, reports that because this is an emerging concept in the multi-family residential sector, he often sees mistakes in valuations. Many appraisers and underwriters want to treat it as traditional multi-family or a traditional subdivision, but it is neither. “The operational data is so important to understand. The expenses and other details are unique to this type of community. You can’t compare it to vertical apartments or subdivisions.” He recommends that appraisers look at comps outside of their market for data if there are none in their immediate area.

Another challenge in developing these properties, and Urbana has one under construction now with 4 more in the pipeline, is in the zoning. The properties don’t fit neatly into most MF zoning, nor do they meet the low-density requirements of most single family home land. “We have to rezone every site,” Urbana’s representative reported. There is often resident resistance in the areas, but once they see and understand the concept, they are receptive.

Unit mix, amenity offerings and location are critical to a community’s success. With the growing popularity of the sector, it is likely that we will see more communities popping up and struggling as errors in judgment become obvious and the potential for overbuilding looms. In the meantime, we can expect to see more and more of these hybrid properties coming to areas all over the sunbelt.

Urbana at Goodnight Ranch, Austin TX