Chris Singleton, MAI, CCIM

Senior Appraiser

Timberland. Many commercial appraisers think they know how to appraise it. They don’t. But we can change that with a few helpful tips. The following discussion from a Cost Approach perspective is part one of a three-part series detailing the basics of timberland valuation. Because land valuation techniques used to develop bare timberland values are the same as other property types, it is ignored here, and the focus is on timber valuation.

First, it’s important to identify what timberland is, how much there is, and where it is. According to the federal government, timberland is the actively managed subset of forestland, which is land that is primarily wooded. The United States has over 800 million acres of forestland, roughly 67% of which is either in active timber production or could be, and is, therefore, classified as timberland. Of this approximately 514 million acres of timberland, about 445 million acres is privately owned, with the remainder owned by federal, state, and local governments.

There are four primary timber-producing regions: the Southeast, Appalachia, the Northeast (inclusive of the Lake States), and the Northwest (inclusive of California and the intermountain region). Each of these regions is very different in terms of species, markets, and timber management practices.

The Southeast is the largest region in terms of geography, production, and value, and is dominated by fast-growing pine plantations. Appalachia and the Northeast/Lake States are slower-growing, hardwood-dominated regions that rely on natural regeneration and selection harvesting, with very little clear-cutting and planting. These are the smallest areas in terms of geography, production, and value. The Northwest is dominated by planted conifers, primarily Douglas-fir and hemlock, with natural pine management, primarily ponderosa, practiced more in drier, slower-growing eastern and intermountain areas of the region. The Northwest has the heaviest component of government-owned land.

It is important to understand that although large timberland properties can be intimidating at first, they are still real property and all three approaches still apply. Like most commercial properties, the Sales Comparison and Income Approaches tend to be the most relevant. A true Cost Approach is difficult to develop on large properties, primarily because of the lack of a market for young timber stands. The following paragraphs briefly walk through the different aspects of a timber property and how to develop cost component values for each.

Merchantable Timber

Merchantable timber is, by definition, timber that is of an age, size, and quality that it can be sold in the market. This applies to planted and natural (not planted) timber alike. The specifications- minimum age, size, quality, etc.- that determine the merchantability of timber are determined by mills and other end users of the timber. This is often the easiest component to value since multiple markets typically exist and prices are frequently transparent.

One way to think about this that may be helpful is to look at merchantable timber like a multi-family residential property.1 An apartment complex has a specific mix of different sizes of units- 1BR/1BA, 2BR/2BA, 3BR/3BA, and so on- and each of these units has a different lease rate. Timberland properties are similar in that they also have a mix of different-sized units, each of which has a different market price. A southern pine property typically has three pine products (units)- pine pulpwood, pine chip-n-saw, and pine sawtimber- with pine sawtimber commanding the highest price as the largest “unit.” The current value of the merchantable timber can be developed by applying contract or market prices to the existing product/unit mix.

For example, assume a 20-acre tract of 27-year-old planted pine has 60 tons of pine sawtimber per acre, 40 tons of pine chip-n-saw per acre, and 25 tons of pine pulpwood per acre. If sawtimber, chip-n-saw, and pulpwood prices are $30, $18, and $8 per ton, then the per-acre value of the merchantable timber: ($30*60) + ($18*40) + ($8*25) = $2,720. The per-acre value applied to all 20 acres results in a total merchantable timber value of $54,400.

Premerchantable Timber

Premerchantable timber, unlike merchantable timber, is not of an age and/or size that it can be sold in the market. Another difference is that young natural timber is rarely considered to have any contributory value, and premerchantable timber value is reserved almost exclusively for plantations. Sales of premerchantable plantations separate from the land are rarely, if ever, seen. Occasionally, leases are made or transferred, representing an exception to this, but such transfers are less common than fee simple land sales, and when they occur, it is difficult to obtain accurate information on the values utilized. There is not an ongoing active market for premerchantable timber separate from land, as there is for merchantable timber. For this reason, premerchantable plantations must be valued in a slightly different way than merchantable timber and are typically valued on a per-acre rather than per ton.

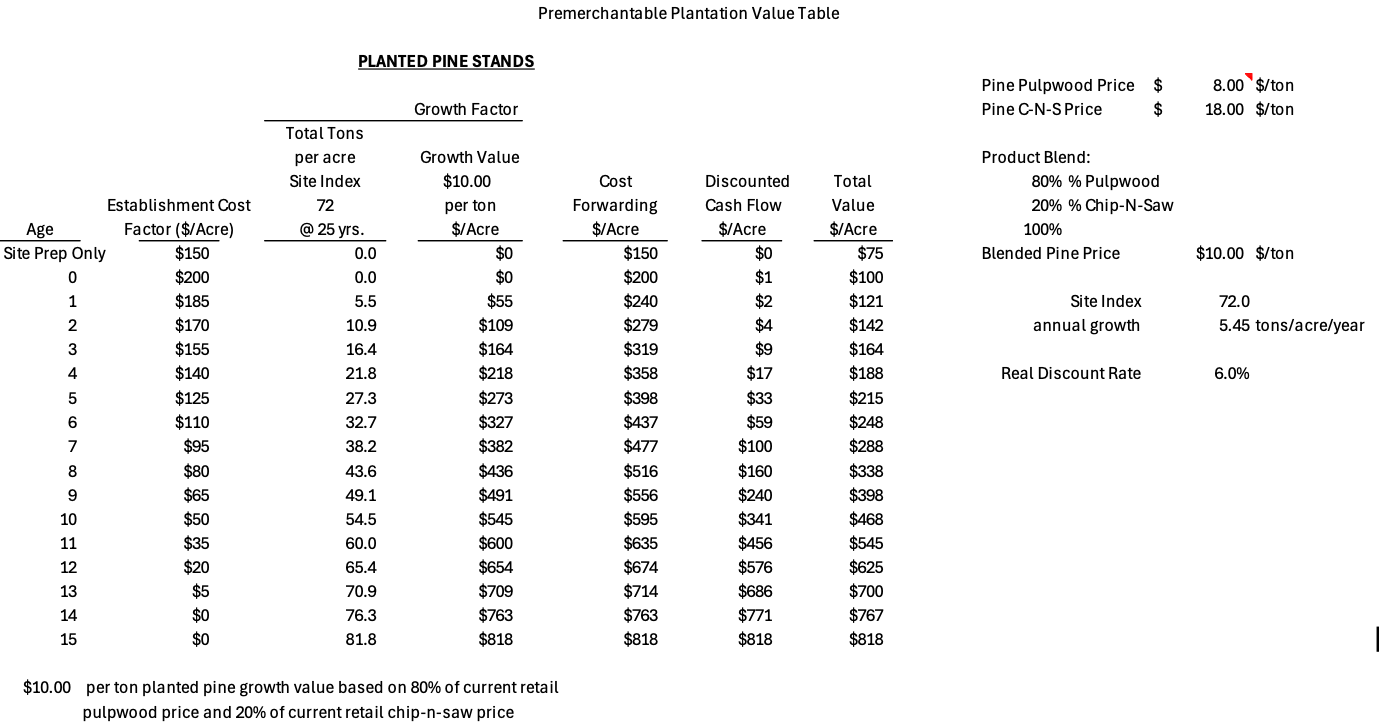

One method of valuing premerchantable timber is via a “cost forwarding plus growth” methodology in which values are based on production per year estimates with an added establishment cost factor. In this method, a percentage of the cost to establish the trees (ie, site preparation and planting) is added to the potential value of the tons per acre at each age, multiplied by a current blended price per ton. The blended price is generally a weighted average of the estimated pulpwood and chip-n-saw percentages at the time of merchantability, which is often considered to be age 15 for southern pine plantations.

A second method of valuing premerchantable timber is to discount the projected value at merchantability to the present age at an appropriate discount rate. This methodology does not factor in any establishment costs and is based entirely on the expected value of timber at merchantability, so the values of very young stands are much lower than they are in the cost-forwarding approach. For this reason, a blend of the two approaches is often used for the final premerchantable timber values. The table below shows estimated market values for premerchantable planted pine acres using both methods, as well as a blended value of the two.

In this table, the establishment cost factor declines as the age increases. This is because in very young stands, close to establishment date, the establishment costs are more evident and are a strong concern for sellers. As premerchantable stands age, getting closer to merchantable size, they are judged more on direct attributes such as growth rather than cost. The discount rate is a real rate, meaning it is net of inflation, which is the standard convention in forestry and timber valuation. The growth factors are based on projections for the estimated growth rate (site index) and stocking (number of trees per acre) for planted stands on the property. The chip-n-saw percentage also reflects expectations for older premerchantable and younger merchantable stands in the region, which is factored into the price applied. The total value per acre presented is the straight average of the two methods, but the weighting can be adjusted according to the appraiser’s interpretation of the market.

If we assume the property has 15 acres of age 7-year-old plantation and another 25 acres of a 12-year-old plantation, then the total premerchantable timber value is simply (15 acres * $288/acre) + (25 acres * $625/acre) = $19,945, or $498.63 per acre.

Conclusion

The total timber value for a property is then simply the total of the merchantable and premerchantable timber values. Using the examples above, the total timber value of the property is $74,345, or $1,239 per acre across all 60 acres. This, when added to the reconciled land value, yields the cost or component value for the property. Since land does not depreciate and timber actually appreciates, no estimates for depreciation, deferred maintenance, etc., are necessary. Timber growth and appreciation will be addressed in the Income Approach in Part 3, after we discuss the Sales Comparison Approach in the next installment.

1Where the comparison starts to break down is that merchantable timber “units” are not static. Whereas little apartment units do not grow into bigger apartment units, little trees do. This is perhaps the hardest part of timber valuation for appraisers not experienced in timber to wrap their heads around- physical growth and appreciation rather than depreciation- but this is not addressed in the Cost Approach and will be dealt with later in the Income Approach.